on

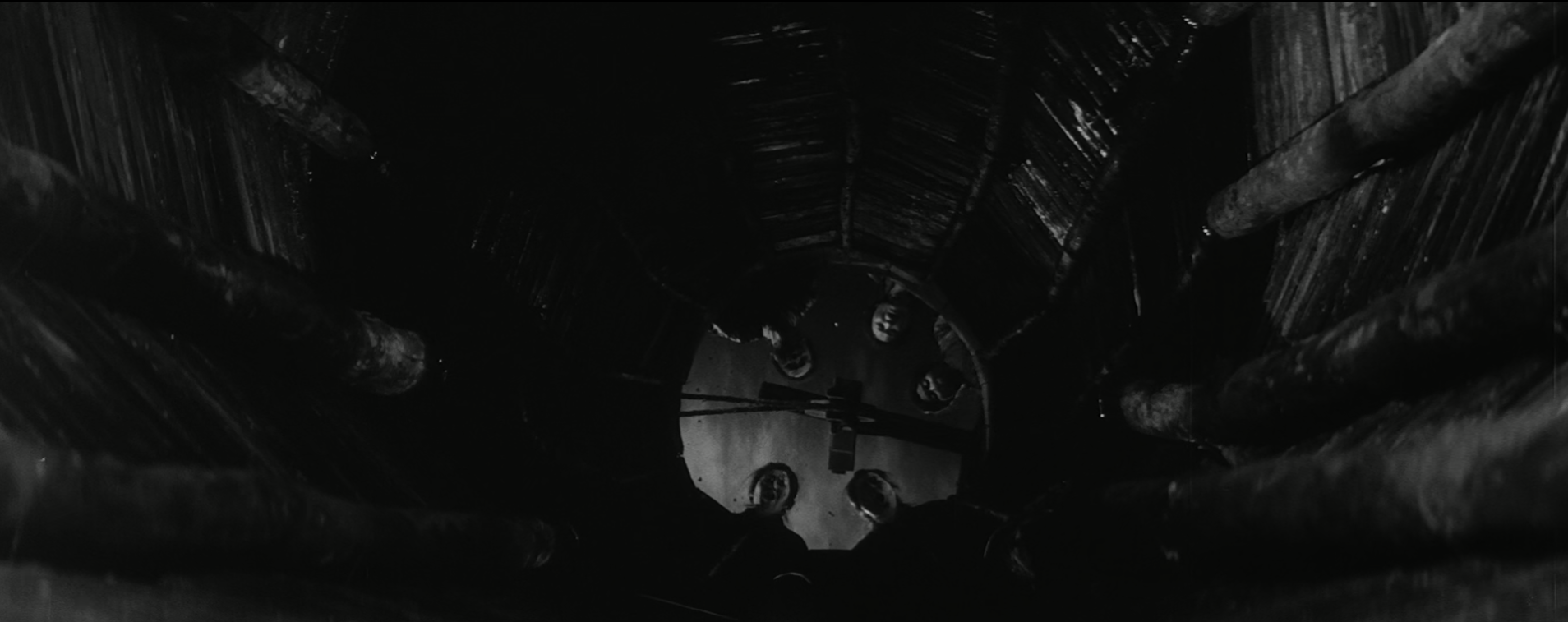

Finding ourselves at the bottom of the well: a beautiful shot from Kurosawa’s 'Redbeard'

What it feels to be like

I wish I was able to face you, the reader, to not be limited by this medium, to yank your arm by force and make you to look into my eyeballs and feel whatever Akira Kurosawa’s “Redbeard” means for me. To make you stay put until you surrender to the beauty of it. I admit defeat: given Kurosawa’s mastery, this piece will never do justice to the movie, the craft or the man behind them.

In a book about Wes Anderson’s “Isle of dogs” (”The Wes Anderson Collection: Isle of Dogs”), there is a two page homage of sorts to Kurosawa - to his movies but also his demeanour: he was a firm man that loved his craft “a man more full, more whole, both more self-willed and more compassionate then most men are”, and I would add an artist at making sincere movies. Sincerity, authenticity, realness, that’s what I thought after seeing Redbeard: simple stories within a main branch, connecting, even if implicitly, honest questions we are faced with in our lives, which were relevant at the time (if not precocious) and still are today:

What constitutes being a good human? What is disease, physical or psychological? How can an individual’s disease be a social problem? How can it be healed? What is privilege, how can it blind us?

The way Kurosawa captures it made me think of David Foster Wallace’s (DFW) description of what really good art should be: “there’s a certain set of magical stuff that fiction can do for us […] one of them has to do with the sense of capturing what the world feels like to us […] it’s the stuff that’s about what it feels like to live. Instead of being a relief from what it feels like to live.” (p38-39, “Although you end up becoming yourself”).

Oscar Wilde said that “All bad poetry springs from genuine feeling.”, which one could generalize to “All bad art is sincere”. There is a fine line between sincere and cringe worthy or lame art, a line which is a constant theme in DFW’s writing since he belonged to a generation embedded in postmodernism - with it’s deconstruction of grand narratives, subjectivity, self-reflexivity, a certain cynicism and ironical distancing - characteristics that were not shared with Kurosawa’s generation. With the lack of shared (religious) narratives that impose values, and the breaking down of truths previously viewed as objective, we were left to ourselves, individually, to construct the meaning and interpretation of the world. But what could potentially be constructive, seemed to Wallace to have never reached that point: postmodernism brought more of itself, it did not seem constitutive to the meaning-making we need to make sense of our lives.

Thinking about Dostoevsky’s work, DFW said “he appears to possess degrees of passion, conviction, and engagement with deep moral issues that we - here, today [americans, late 1990] - cannot or do not permit ourselves” (p271, ”Consider the Lobster”) to which he contrasted the US writing culture, which was not nihilistic per se, but rather suffering from a “congenital skepticism”. To DFW, being sincere in his timeline was - even more than potentially making bad art - to risk not being taken seriously, to be shrugged off with “a raised eyebrow and a very cool smile” (p273, Ibid). But Kurosawa, like Dostoevsky, was not yet in the postmodern zeitgeist, that’s why his movies give a specific shine of rawness.

What DFW tried to capture in his fiction was a conjunction of both the modern and postmodern worlds: one both sincere and skeptic, raw and reflexive, to be fully open to the emotions of the scenes but critical of what they are portraying - a trend that developed into the late 00’s and 10’s of the 21st century where it “now seems to [exist] a search for meaning while still holding onto the idea that there is no [single] truth”. This piece of writing is an attempt to view Kurosawa’s Redbeard under this lens, alternating perspectives midway.

What it is about

The movie develops during the Edo period in Japan, a period of two centuries between the 17-19th centuries in which only Chinese and Dutch representatives could dock and trade in specific ports in Japan.

Noboru Yasumoto is a young doctor that had spent 3 years studying western (Dutch) medicine in Nagasaki and was promised a position high up in the shogunate - the military dictatorship structure that ruled the country. Instead he finds himself as an assistant to Dr. Kyojo Niide aka Redbeard, in a shody clinic with little funding in the countryside, called Koshikawa clinic. Yasumoto faces harsh conditions on what seems a non-reputable job and initially refuses to accept the situation, claiming there was a mistake. This is shown not only through the plot but also through the photography: on two shots there is a visual divide between the characters arguing, as he is still convinced he’s in the wrong place (notice the exact same body language).

The main thread of the movie follows Yasumoto as he confronts situations that force himself to reconsider his privilege and this is where the pace of the movie picks up. The first is an old man called Rokusuke that was unable to even pronounce a word as he was dying from cancer and nothing could be done to save him. Despite being a former renowned goldsmith, no one came to visit him on his deathbed, which prompts Redbeard to get angry at the lack of resources and impotent facing the state of the world, eventually sighing “There is always a story of great misfortune behind illness […] His heart probably hurts him even more”, with “heart” here not to be interpreted literally - hinting at a motif that gets repeated across the movie: mind and body intertwined.

Left alone in the room, Yasumoto cannot fathom the direness on Rokusuke’s face.

Eyes closed, squinting with the force of pain

Beard, hair, mind astray

the wrinkles - each a tear a solitude away

Gum with no teeth,

exhalation brings no relief

A gasp of mouth with no sound

what of those supposed to be around

Eyes open, staring into infinity

this is where I’ll be for all eternity

Almost collapsing in horror, Yasumoto flees the scene. Later, he discusses Rokusuke’s death with an assistant doctor which confesses him that “The pain and loneliness of death frighten me. But Dr.Niide [Redbeard] looks at it differently. He looks into their hearts as well as their bodies. He saw great misfortune behind his silence”. This phrase has immense symbolic power, to me it’s almost as when Redbeard listens to his patients, their diseases echo within him. Echoing here having two interpretations. One is that their diseases, which share a common “story of great misfortune”, are a reflection of those of society: we can’t help but feel some responsibility, some burden for what happened to that person since we are part of a society that enabled this to happen - we are accomplices, even if implicitly or passively. Another, focused more on the individual, is that in order for us, as humans, to understand one another and to heal our own individual pain, we need to echo the emotions that certain moments trigger in us. Redbeard - as a doctor that also cures problems beyond (or rather, intertwined with) the physical ones - lets the moments resonate within, since these moments also tell something about him - they give a reflection of him back, in this case via anger and resentment. And this double meaning of “echo” potentiates the most beautiful shot in the movie.

The well shot

The shot revolves around two characters: a young girl called Otoyo who was rescued from a brothel by Redbeard and Yasumoto, and Chobo, a kid belonging to a family of five that live in extreme poverty, being unable to provide food for themselves. The two meet when Chobo tries to steal food from the clinic’s kitchen, an encounter in which Otoyo clearly understands Chobo’s situation and instead of scolding him or alarming others, she pretends he’s not there.

Their friendship strengthens as Otoyo shares the daily dinner leftovers with him. As a way of thanking her, Chobo steals a couple of lollipops from downtown to offer her - a scene witnessed by Yasumoto and one of the cooks spying in the back. Otoyo accepts them, only to offer them back, saying that he needs them more than her. It’s a beautiful shot because we see Chobo’s intention (his hand holding the lollipops) but not Chobo itself. There is also depth in the scene with Chobo and Otoyo on a plane separate from Yasumoto and the cook. It is one more situation in which Yasumoto realizes his own privilege, being distraught by how naturally Chobo deals with the misery of his life: simultaneously sad but also pragmatic and mature. When Otoyo says Chobo’s parents are terrible people for not providing for him, he neutrally responds “Don’t say that. They can’t help it. They’re so poor that they’ve gotten stupid”.

Despite this bond, one day Chobo comes to visit Otoyo at night. Chobo’s demeanour is generally one of stark ephemeral expressions of happiness, repent, guilt or that look of pride only children can feel for minute things. However, in this scene, he is slump, muddied, dull faced and above everything elusive and avoidant. “We’re going somewhere nice. It’s far away, but we don’t have to worry about food and it’s fun out there” he shares and proceeds to explain the wonders of this place to Otoyo. When she doubts him, he changes subject and screams at her not to move, so he can remember her for a long time before going. On a frontal shot as we walks backwards away, we see Chobo’s emotions wave between resolved, apprehensive, grateful, filled with awe, sorrow, ending in that expression of tension that can only insufficiently be capture by “bitter sweetness”: a melancholic gaze of saudade for a never-fulfilled future. And one can’t help but to feel gutted when he runs away.

This tension culminates into the well shot. Later on, Yasumoto is called for an urgency and realizes Chobo’s family poisoned themselves - Chobo is on the verge of death. Laying beside him crying, Otoyo hears screams from outside and runs there. “There’s a belief that if you call into the well, you can call a dying person back. Wells lead to the core of the earth”.

The well shot pictures Otoyo and the cooks crying around the well, seen from below, with Kurosawa’s lens pointing towards the sky. As they scream, the camera slowly rotates inside the well, eventually aiming at the water which gives them their reflections back, until a tear drops and forms ripples in the water while the shot fades to black.

The scream, the reflection, the echo and the ripples are all part of the same symbolic family that gives the shot its power. The screams (sound) are both an attempt at saving the boy but also a cathartic way of coping with the pain and anguish of Chobo’s potential death. They reflect across the well and echo back. Their faces (image) are also reflected back to them - they see themselves suffering - but mourning someone’s death is never “just” about their departure. It is also a confrontation with one’s own fears and shortcomings, regrets and achievements, our idiosyncrasies and mannerisms. Other people enable us to see ourselves: when they’re gone, their (our?) reflections are carried with, leaving a void behind. They resonate, ripple within us.

When witnessing or suffering pain, when we find ourselves at the bottom of the well, maybe it’s there, pooling from the reflections that others give of us, that we manage to construct and see our selfs.

Epilogue

The end of the movie ends on happy terms: Chobo lives and Yasumoto finds his fulfillment in working in the clinic helping others. However there are two moments in the narrative that can’t help but upset the warm feeling of loose ends tied. These are the moments in which the lenses of a newer generation interpret situations differently.

A major arch of the movie concerns Sahaci, a patient that is very sick but keeps working to provide for the other patients in the clinic. His health state worsens to the point where his death is inevitable, and one night, under heavy rain, a landslide occurs right in front of his hut. When people discover a skeleton in the mud, Sahaci silently confesses to Yasumoto that it is his wife’s body - “she has come for me”. After gasping for breath he asks Yasumoto to gather everyone for him to tell his love story in order to die in peace.

The scene is sombre and beautifully lit with a gradient from the left to right, from the living to the darkness awaiting; Sahaci in between.

A long time ago Sahaci had fallen in love with a woman, Onaka, that was tied to an arranged marriage, which she concealed from him. As the feelings were reciprocal, he convinced her to marry him, but time after time she kept refusing to introduce him to her parents, much to Sahaci’s despair. The relationship went on until there was a great earthquake. Sahaci, unable to find her body in the rumbles, assumed she was dead. However, years later he finds her at a local market, gasping seeing she was carrying a baby. They barely exchange words, it was clear. Impotent about the situation, Sahaci turns to drinking, yet a few days later she comes alone to his house and we hear her side of the story. She felt indebted to the man she was arranged to and - despite loving Sahaci while they lived together - always felt that punishment for “fleeing” would come one day, that things were too good - “A girl like me did not deserve it”. She had interpreted the earthquake as a sign of punishment, and left for her old life. At the end of the story she asks Sahaci to hug her strongly whilst, unbeknownst to him, carefully hiding something in her hand - a knife pointing at herself. She stabs herself with the force of Sahaci’s hug and dies on his arms with a macabre look straight at the camera.

Throughout his life Sahaci blames himself for her death, but also for the suffering caused upon her husband and child. It’s a scene about how even “good” people do “bad” things: how the wholeness of a good human cannot be made in a vacuum without the bad things that characterize us - “We need to observe how a man who thinks of himself as flawed can be wholly good” (source). Here one has to note how “good” and “bad” are labels, constructs imposed upon Sahaci and fully embodied by him, because, inherently, his actions are neither.

But the key point is not this one, but rather Onaka’s train of thought. I can’t stop thinking that this part of the narrative feels a little quaint. The dramatic tensions rests on the premise that Onaka can not tell Sahaci about the planned marriage (by fear of him leaving her, or her parents deserting her, these being the only options in her head [were they really?]) It’s most probably a generational gap but at this point most Millenials/GenZs would be pulling their hairs in disbelief asking “why can’t they just talk about it? Why can’t people face their issues without sweeping them under the rug?!” Onaka’s narrative of lack of self-worth, of fulfilling a duty due to being “indebted”, carrying the guilt cross, accepting “punishment” because of a decision that she made to free herself from others’ impositions; this narrative doesn’t quite hit the younger generations, which share different values regarding self empowerment and social norms, generations whose first thoughts would be “why didn’t she go to therapy?”.

In generations where rigidity of structures are broken across levels - religion, core family, intimate relationships - where thoughts and impulses aren’t buried and labelled as “sins” or “wrong”, one can’t help but think that different outcomes could have yielded from these circumstances. And for this I think this narrative feels a bit artificial - even though it is a portrayal of the Edo period, even though it is a movie - the “suspension of disbelief” that we all practice when consuming any fiction media breaks down, and it somehow seems a romanticization of pain.

As a final comment, the opening and closing shots mirror each other, with Yasumoto going through the gates of the clinic, now a different man. This gives the watcher a feeling of circularity, the end meets the beginning again, and since “All’s well that ends well”, we get that warm, fuzzy, cozy, happy, pacified reality-is-saved-afterall feeling. But it’s not. The clinic still has little funds, the poor are still there not because they are inherently sick, “stupid” or fragile by nature, but because poverty makes them sick and the only person to get better off is the one that was already that way to start with. Yet, it’s not Yasumoto’s fault either - seeing it that way would be a mistake provoked by a system whose nature entices humans against each other in order to yoke their hability to identify the core problem: inequal wealth distribution under a capitalist system. (The screenplay itself suffers from this capitalistic disease with its focus on the main character, the individual, having a good ending.) Echoing Mark Fisher’s words: “By privatizing problems - treating them as if they were caused only by the individual’s neurology and/ or family background - any question of social systemic causation is ruled out” (source).

The movie is beautiful - its rawness grips us, we (viewers) learn about our nature as we go, it even manages to be comical at points - it is meaningful. Nonetheless, the main thread connecting the stories is a “coming of privilege” story in which privilege ends up reinstating itself.

I would like to acknowledge Margarida Brotas for comments and ideas on an earlier version of the piece.